The taxes paid by Montana residents and businesses have created and continue to fund an equitable educational system, roads and bridges, and services that keep our communities safe. Unfortunately, over time, responsibility for our tax system has shifted to everyday Montanans, like our teachers, plumbers, and construction workers, and away from the wealthy.

Over the last three decades, Montana lawmakers have eroded our tax base and shifted tax responsibility onto the backs of Montanans with low and moderate incomes. At the same time, the wealthiest have gotten away with substantial tax breaks and loopholes. This should come as no surprise, as those who can afford representation in the Montana Legislature are not your everyday heroes like our firefighters, child care providers, and nurses, but special interests with access to wealth and resources. Day in and day out of the Montana legislative session, big business and the wealthy hire lobbyists to appeal to legislators to get a piece of the tax cuts dealt out. Unfortunately, legislators have overwhelmingly granted these appeals over time, resulting in the Great Tax Shift.

Cutting Income Taxes for the Wealthy

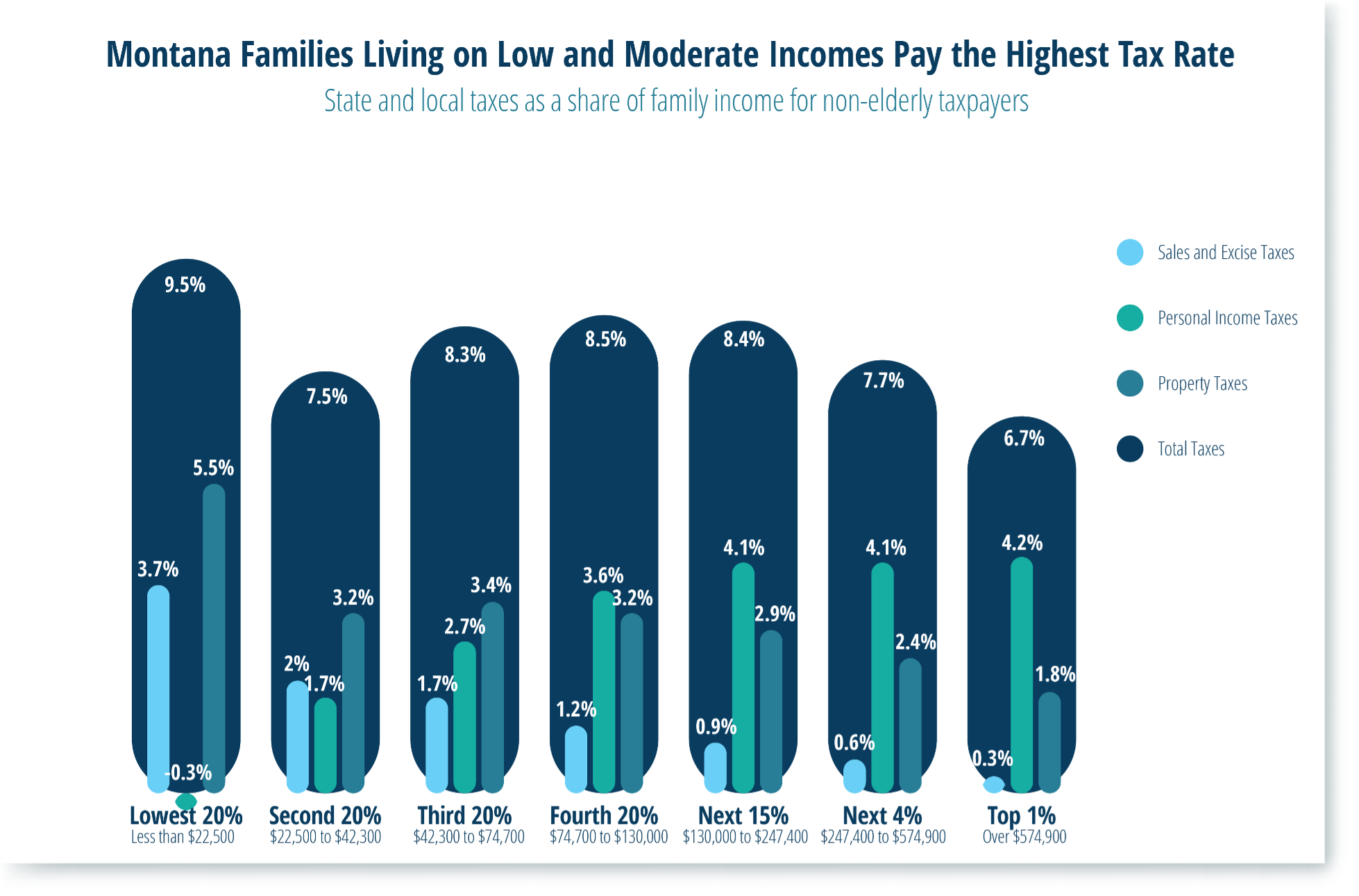

Montana’s state and local tax system asks those with the least to pay the highest share of their incomes in taxes. Montana families with the lowest incomes are paying an effective state and local tax rate of 9.5 percent, while the wealthiest pay 6.7 percent.[1]

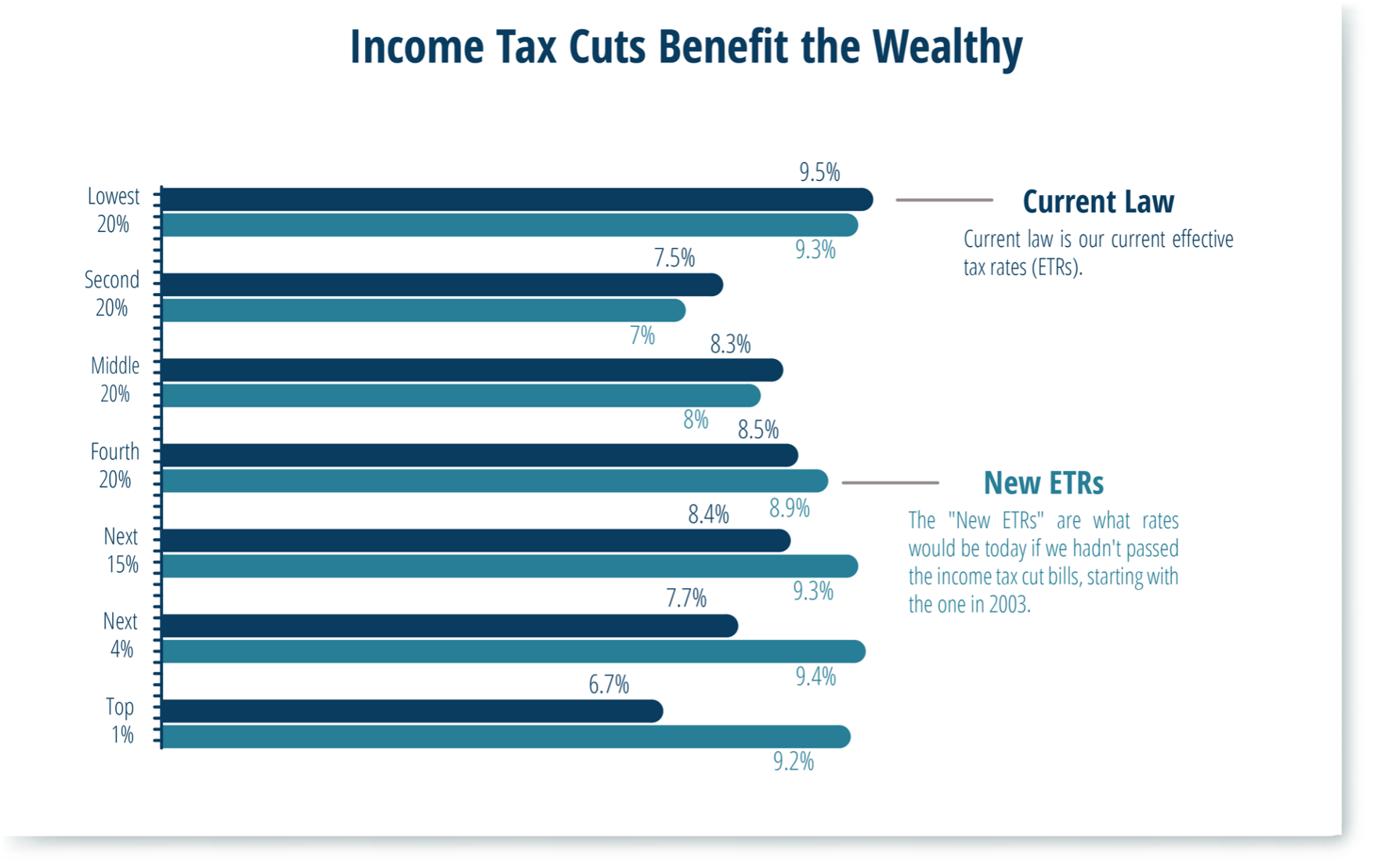

However, this was not always the case. The last two decades in Montana have brought about great change to the tax system, and most of this change has benefitted the wealthiest over everyone else. The most significant piece of this change happened in 2003 when the Montana Legislature passed a bill that seriously altered the state tax system. The changes made in 2003 included collapsing the income tax brackets and creating a tax cut for capital gains income.[2] Both of these provisions resulted in a big tax cut for the state’s wealthiest residents. These tax cuts have cost the state nearly a billion dollars in the following decade, which could have been used to invest in Montanans through education, health care, housing, and more.[3] Before this significant tax cut was passed, Montana’s tax code was much more evenly structured. While families with the lowest incomes still paid high tax rates, those tax rates carried through to the wealthiest Montanans.[4]

Montana’s income tax system remained relatively unchanged for the following years until the 2021 and 2023 Legislatures resumed throwing taxpayer dollars at giveaways to the wealthy. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the existing racial wealth gap. Contributing to this trend of increasing wealth inequality, Montana’s 2021 Legislature passed an income tax cut that went primarily to white, wealthy Montanans. Nearly 80 percent of the benefit of the income tax cut went to the wealthiest 20 percent of Montanans, who are disproportionately white because of a history of policymaking that favors whiteness.[5] The 2023 Legislature continued this trend, further cutting the top income tax rate and disproportionately benefitting the wealthy. The top 1 percent, those with incomes in excess of $650,000 a year, are expected to get an average tax cut of nearly $7,000 each year, while those with incomes up to $81,000 will get less than $85 on average, enough to cover a tank or two of gas.[6] Seventy percent of this ongoing tax cut will go to the wealthiest 20 percent.

Regressive tax structures, like Montana’s, contribute to growing income inequality. Households with lower incomes are required to pay a greater percentage of their incomes in taxes, while the rich can use more income to increase wealth levels even further. At the same time, rising income inequality contributes to slower, more volatile state revenue growth.[7] Income tax from the wealthy often comes from capital gains, which are more subject to ups and downs than income from wages and types of income received by people with low and moderate incomes. Also, the higher savings rates of the wealthy mean that increased income in wealthy households is less likely to induce consumer spending than income for families with low and more moderate incomes. Since one person’s spending is another person’s income, income inequality slows personal income growth despite increasing incomes at the top.[8]

Property Taxes Shifted to Renters and Homeowners

Property taxes are an essential revenue source for our local schools and governments, helping communities from Hamilton to Havre to provide quality, equitable educational programming and maintain roads. Property taxes are, by nature, a regressive tax, meaning that families with low and moderate incomes pay a higher share of their incomes in property taxes than the wealthy.[9] There are numerous reasons for this, but most basically, those making lower wages have to use more of their income to pay for housing.[10] For example, a middle-income family wanting to own a home may have to buy a home five times their annual income, while a wealthy person’s home may be equivalently valued to their annual income or much less. Another important thing about regressive property taxes is the fact that renters pay property taxes through their rent, so growing housing costs impact renters as much, or in some cases more, than their landlords.

In Montana, the share of property taxes paid by residential homeowners has increased in recent decades. In contrast, the percent paid by other types of property classes, such as large corporations, has declined. This shift has come into play for a variety of reasons. First, the values of residential homes have been increasing faster than other types of property. Local government budgets are like a pie, and when one class increases in value, it makes up a larger share of the pie, reducing the shares the other classes of property are responsible for.

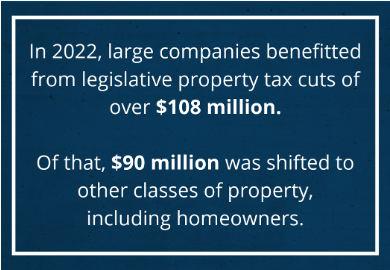

Second, over the last three decades, the Montana Legislature has enacted many property tax cuts that have resulted in an overall shift away from business property to residential. Tax exemptions put in place from  1989 to 2023 contributed to the increased reliance on residential property. These include tax exemptions like the intangible personal property exemption, tax rate reductions, and exemptions on business equipment property. In 1999, the Legislature changed the law to exempt certain components of the value of a business in calculated property taxes.[11] Policymakers expanded the law to include larger businesses, including large telecommunications and utility companies. The impact of this policy has resulted in a significant reduction in property taxes for larger companies. In 2022, large companies benefitted from tax reductions of over $108 million from this exemption, $90 million of which was shifted to other classes of property, including residential, contributing to the tax shift.[12]

1989 to 2023 contributed to the increased reliance on residential property. These include tax exemptions like the intangible personal property exemption, tax rate reductions, and exemptions on business equipment property. In 1999, the Legislature changed the law to exempt certain components of the value of a business in calculated property taxes.[11] Policymakers expanded the law to include larger businesses, including large telecommunications and utility companies. The impact of this policy has resulted in a significant reduction in property taxes for larger companies. In 2022, large companies benefitted from tax reductions of over $108 million from this exemption, $90 million of which was shifted to other classes of property, including residential, contributing to the tax shift.[12]

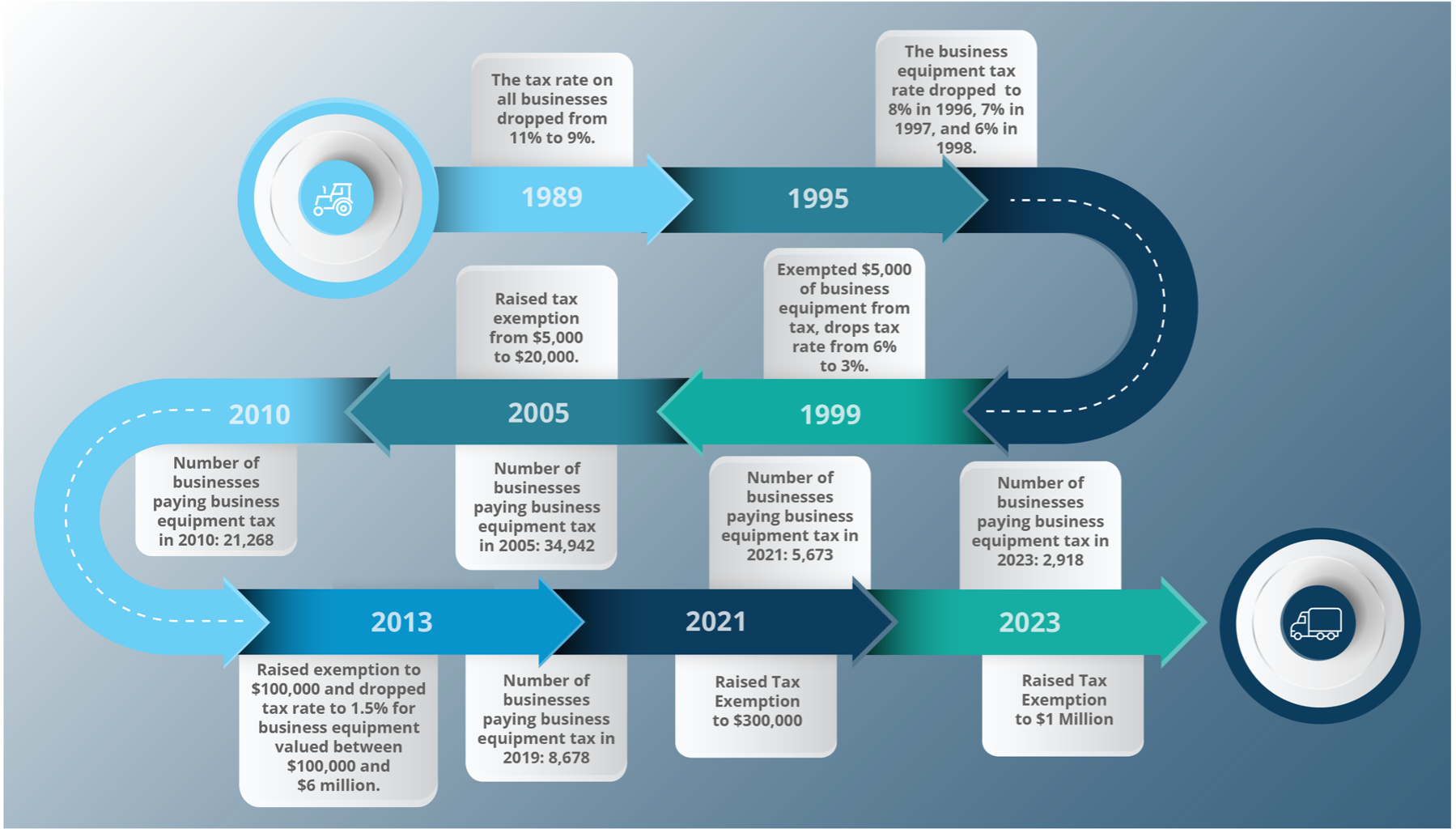

Business equipment is one class of property that has benefitted from tax reductions numerous times in recent decades. From 1989 to 2024, the Montana Legislature has cut business equipment taxes nine times through reduced rates and expanded exemptions. Today, the first $1 million of business equipment is not taxed, business equipment valued between $1 and $6 million is taxed at 1.5 percent, and business equipment valued over $6 million is taxed at 3 percent.[13] These increasing exemptions have reduced the number of businesses paying business equipment tax from 18,444 businesses in 2008 to 2,918 in 2023.[14] There were likely many more businesses paying business equipment tax before the first exemption was passed in 1999.

These are just two examples of the numerous policies and practices that exacerbate property tax regressivity, asking homeowners and renters to pay more while owners of business property pay less. Some of these specific proposals may not have immediately increased the reliance on residential property because they were coupled with laws requiring state funding to backfill local government budgets. However, the policies increased the property tax system’s reliance on residential property over time and shifted tax responsibility away from business owners and to general fund contributions, much of which is made up of revenue from individual Montanans through individual income tax.

The Montana We Could Be

With public awareness focused on rising residential property taxes and housing costs skyrocketing, the time is ripe to demand the powerful pay their fair share. We all benefit when our communities are safe, our kids are well-educated, and we have safe roads and bridges.

Luckily, we can make many simple reforms to stem the tide of the great tax shift:

[1] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Montana: Who Pays? 7th Edition,” Jan., 2024.

[2] Montana 58th Legislature, “Income Tax Reductions with Revenue From Limited Sales Tax,” SB 407, enacted on Apr. 30, 2003.

[3] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Montana Personal Income Tax Revenue Lost, 2005-2016,” MBPC information request, on file with author.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Model of SB 407,” MBPC information request, received on Jan. 18, 2024, on file with author.

[5] Bender, R., “Racist Roots of Montana’s Tax System,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, Dec. 2022.

[6] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Model of SB 121,” MBPC information request, 2023, on file with author.

[7] Petek, G., “Income Inequality Weighs on State Tax Revenues,” Standard and Poor’s Ratings Services, Sep. 15, 2014.

[8] Petek, G., “Income Inequality Weighs on State Tax Revenues,” Standard and Poor’s Ratings Services, Sep. 15, 2014.

[9] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Montana: Who Pays? 7th Edition,” Jan., 2024.

[10] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? 7th Edition,” Jan., 2024.

[11] Department of Revenue, “Biennial Report, July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2022,” Dec. 15, 2022.

[12] Department of Revenue, “Biennial Report, July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2022,” Dec. 15, 2022.

[13] Mont. Code Ann., 15-6-138.

[14] Dale, E. and Cole, D., “Big Centrally Assessed Taxpayers,” Department of Revenue, Feb. 6, 2024, on file with author.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.